The Shadow Banking System

Shadow banking is the name given to an informal system of credit creation, financial trading, speculation and investment that occurs outside of traditional banking and it lies at the very heart of the global economy. Shadow banking falls outside the realm of traditional banking regulations and oversight. The shadow banking system consists of hedge funds, private equity, securitisation, derivatives, equities, speculation and more, it accounts for over half of global banking assets and represents a third of the global financial system. How this system operates and its origins are shrouded in secrecy and lies far beyond the purview of the average person and this is precisely why l have proposed this series.1

The shadow banking system is highly integrated, operating around the globe, it is both extremely secretive and elitist (as one might expect). However, though it is all around us it remains invisible to the naked eye. Operating out of global financial hubs like London, New York, Tokyo, Singapore and others, the effects of shadow banking can be observed throughout the world.

As a result of the deregulation of the banking system in the 70s and early 80s, a web of intricate and highly secret trading networks started to develop and various complex financial instruments slowly began to emerge. These include, among others: credit default swaps (CDS), hedge funds, collateralized debt obligations (CDO), special purpose vehicles (SPV), money market mutual funds (MMF), securities of various kinds, structured investment vehicles (SIV), private equity firms and more. The shadow banking system grew in prominence throughout the 80s and 90s and the politicians and business leaders moved in lockstep with it. The traditional economy based on trade in goods and services slowly started to subside making way for a new global economy based on cross border capital flows and speculation. It is not confined to just the financial sector either; consider that McDonald’s no longer just make hamburgers and Nike do not solely make sports apparel: they have huge asset portfolios across a range of markets around the world and it is the same for most multinational companies. These diverse portfolios will consist primarily of financial assets, but will also include property, commodities and other investments as well, that will likely generate as much income as their primary activities do (and in many cases actually a lot more). This is simply the reality of the world we inhabit today and there is no denying it.

In the past, banks and financial institutions used to facilitate the market and enable capitalism: now they are the market and financialisation is the new capitalism. Advanced economies now produce financial products and provide financial services instead of real goods and services (in the traditional sense), this is the reality of the world we are in today. Consider that BlackRock controls $11.5 trillion of assets and Vanguard controls $10.4 trillion of assets, respectively. Like many of the major investment companies, index funds and asset managers (alongside Vanguard and BlackRock, Capital Group [$2.6 trillion in assets] and State Street [$4.7 trillion in assets] also deserve a mention), the scale at which they operate is unparalleled, the bigger they are the more assets they control and the more power and influence they have as a result, and by the same measure the harder it is to compete with them. In many cases, these institutions control more assets than the GDP of many countries.

A study by the Harvard Business School estimated that private equity is estimated to control as much as 20% of the U.S. economy and, in the words of The Atlantic, a large segment of the economy that is effectively “invisible to the media and regulators.” 2

Financialisation has ended the age-old idea that governments can control the economy simply by raising and lowering taxes, by adjusting spending or through other policy measures. Undeniably, since the 1980s there has been a transfer of power from the political sphere to the banking one, as banking and finance increasingly exerts more influence over the economy.

Political elites are partial to shadow banking because a large and growing stock market inflates the economy: as financial assets rise in value so does the GDP of that country, so the stock market is used as a means of inflating the economy, making it appear more prosperous than it actually is. Opposingly, countries that don’t have deep and sophisticated money markets are at a sizable disadvantage compared to those that do. On the ground level, it is only safe to assume that those in politics and business are presented with attractive investment opportunities by their peers in finance and banking, which is simply the reality of how elite power operates.

Origins

The origins of the shadow banking system are complex and numerous. It can be traced back to:

· the re-emergence of global capital markets in the 1960s,

· the collapse of the Bretton Woods system,

· the end of the gold standard in 1971,

· the expansion of the market for U.S. Treasury bonds in the mid-1970s,

· falling interest rates in the early 1980s,

· and financial deregulation during the 1980s and 1990s.

We will look at each of these separately.

The Bretton Woods era

The collapse of the Bretton Woods system marks a very important moment in the rise of shadow banking. During the Bretton Woods era, cross-border capital finance was heavily restricted but trade was encouraged and remained free, exchange rates were fixed against the dollar with the dollar tied to gold, and finally all of this was overseen by largely impartial bodies like the IMF. Capital controls formalised at the Bretton Woods conference were observed by and adhered to by all the member states and the stability that all of this brought led to growing prosperity in both Europe and America. During this time, there was no fear that money would flee overseas looking for better rates and higher returns as the Bretton Woods system was designed to contain this. Financial regulation was tight and closely monitored and ultimately national governments oversaw everything in the economy. This era is known as the Golden Age of Capitalism defined by high growth, low inflation, low unemployment and prosperity shared by almost everyone. Financial crises were infrequent and debt were low as well.

However, one group was certainly not very happy with this system: the bankers. From Wall Street to the City of London, those in high finance were none too pleased with this arrangement. In response to the Keynesian consensus, a group of radical economists rallied around the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek’s ideas about free market economics; namely, markets free of government interference and based around competition, guided by Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’. In practice, this meant privatisation, deregulation and cutting social spending, as well as lowering taxes in the process, the name given to this radical new approach was called ‘neoliberalism’. Neoliberalism is the precursor to globalisation, the free movement of goods, people, ideas and, most importantly of all, capital. Shortly after the Bretton Woods conference, these economists would go on to form the Mont Pelerin Society (named after a small locality near Geneva, Switzerland), the group included among its luminaries the likes of Ludwig von Mises, Karl Popper, Milton Friedman and George Stigler. Their meetings were funded by, among others, some of Switzerland’s top banks, the Swiss central bank, the Bank of England and those drawn from high finance from the City of London. They wanted banks to capture the market by unleashing global capital from the shackles of Bretton Woods and the Keynesian consensus. From this moment on, floods of money would pour into think tanks on both sides of the Atlantic advocating for neoliberal ideas. Milton Friedman would go onto to influence many American presidents (perhaps none more so than Ronald Reagan) and Margaret Thatcher would extoll the ideas of Hayek repeatedly during her time as prime minister of Great Britain.3

During the Bretton Woods era another significant development would take place, namely the rise of offshore dollar holdings that had little regard for the official peg or the Bretton Woods consensus more broadly. Called the Eurodollar markets, this was the name given to large volumes of U.S. dollars that accumulated in London, outside of the U.S. and beyond the reach of the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury. Over time, the Eurodollar markets would outgrow the existing banking infrastructure as a source of wealth and financial power. The Bank of England turned a blind eye to these deposits, they weren’t taxed and they weren’t regulated and it should come as no surprise to learn that the Eurodollar markets saw large inflows from individuals and entities related to crime, the black market and tax cheats. Additionally, those who stood opposed to the United States on the Cold War chessboard – namely the Soviet Union and China – were thrilled at the prospect of not having their dollar accounts regulated by the U.S. Significantly, Eurodollar markets offered higher interest rates and thus higher returns than in the U.S. and as a result dollars poured in from the United States, accelerating the end of the Bretton Woods system.4 Consequently, and contrary to the Bretton Woods protocols, global capital markets slowly started to re-emerge in the 1960s, a parallel system of finance that could offer preferential rates and favourable terms and conditions for borrowing and lending. Cross-border capital flows exploded, between 1963 and 1969 U.S. bank deposits in London grew twentyfold as billions of dollars began circulating across international markets. The Eurodollar markets were not closely monitored, and they quickly became the centre for unregulated deposit taking and lending.

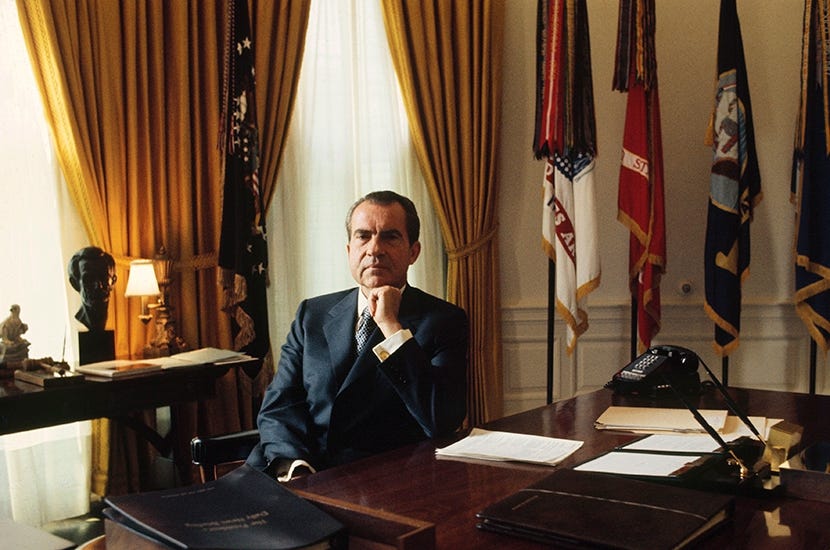

The end of the gold standard in 1971

The rise of shadow banking really began with the end of the gold standard in 1971. In August 1971, President Richard Nixon abandoned the dollar’s link to gold, ushering in the era of floating, fiat currencies, alongside fluctuating interest rates. Without a solid, metallic base to it, money creation would expand beyond anyone’s wildest imagination, every level of finance was reshaped by this decision, including the big investment and commercial banks. Allowing currencies to float as a result of removing the exchange rate system led to the enormous growth in international finance and cross-border capital flows, this in turn led to a broadening and deepening of financial markets through the 1970s.5 And since 1971, banking assets as a share of GDP have consistently grown. Those who are familiar with my work probably know that I have written extensively about this moment numerous times in the past.

The expansion of the market for U.S. Treasury bonds in the mid-1970s

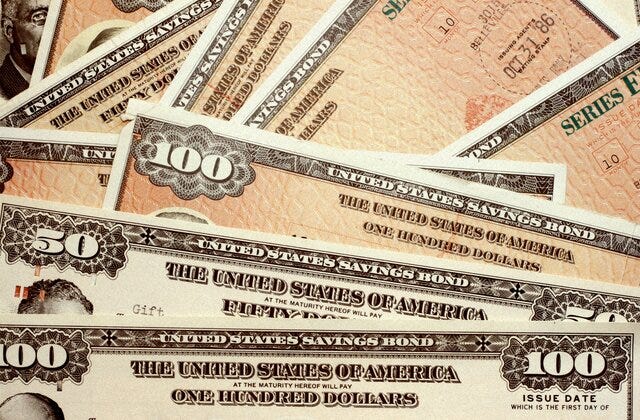

The advent of the petrodollar along with the expansion of the market for U.S. Treasury bonds in the mid-1970s would further redefine the landscape of global finance. The petrodollar agreement between the United States and Saudi Arabia (and eventually the other OPEC nations too) meant that oil was now tied to the dollar, and if you wanted to purchase oil then you needed dollars to do so. Furthermore, the petrodollar agreement stipulated that excess dollars would be reinvested into the purchase of U.S. debt, primarily into U.S. government-backed Treasury bonds by the OPEC member states, and as a result U.S. Treasury bonds became the primary reserve asset in the global economy. As a result of all this, the market for U.S. Treasury bonds exploded, and as these bonds promised a small amount of interest with their purchase, as such they were a natural outlet for all the excess dollars that had built up during the Bretton Woods era.

Suddenly, commercial banks were flooded with fresh liquidity and credit, and billions of excess dollars were available for investment and for speculation in the money markets and overseas. The growth in the bond market laid the provided a new and enhanced role for investment banks and other financial intermediaries in the global economy, and to accommodate these large inflows of dollars, new capital investment institutions were founded to assist the major Wall Street banks, chief among them were Vanguard (founded in May 1975).6 Eventually, other countries would sign up to this agreement as well and today over $900 billion are traded daily in U.S. Treasuries, with U.S. government-backed Treasuries being the most liquid, in-demand financial asset available (by some measures, only the market for oil has a higher trading volume).7 It is also worth mentioning that around this time, fixed fees charged by Wall Street brokers for trading stocks were abolished.

Lastly, during the 70s new derivatives markets allowed for the spreading and hedging of risk and the development of new securitised financial instruments as well such as money market mutual funds (MMFs) which helped circumvent New Deal-era “Regulation Q” ceilings.8 We will return to the U.S. bond market a bit later.

Falling interest rates and financial deregulation during the 1980s and 1990s

During the 1980s, neoliberal reforms continued, and under the Reagan administration the banking sector was heavily deregulated and banks took on a new prominence in the global economy as a result. Banks were at the forefront of globalisation and the free movement of goods, capital and people, helping markets expand across borders. During this decade, the regulatory framework established in response to the Great Depression in the 1930s, along with the final remnants of the Bretton Woods system, started to be dismantled.

However, the 80s began with the Volcker shock, as Fed Chairman Paul Volcker raised interest rates to record levels in a bid to conquer inflation. During the Great Inflation banks were forced to shift their focus from traditional lending (like mortgages and loans) to trading in bonds, commercial paper and securities. Canadian authors Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, in their excellent book The Making of Global Capitalism (Verso, 2013) remarked that, “This was also crucial to turning investment banking into a much more speculative business.”9 The end of the Great Inflation was a benefit to everyone; as rates came down borrowing became cheaper, and more borrowing means more spending and this means more money circulating in the wider economy.

Reagan and Thatcher wanted a market-based model for banking and finance just like the one for industry. To achieve this, the finance sector needed to be deregulated and so it was: key legislation was reinterpreted, standards were lowered and by the early 80s all restrictions on capital movements were abolished. It was round about this time that many of the more complex financial instruments started to evolve as well.

The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 mandated the separation of commercial and investment banking, and the Reagan administration started to repeal large parts of this act (something that would reach its climax during the Clinton administration). When Glass-Steagall was overturned, the rule book on banking and finance was effectively re-written. This began early into Reagan’s term when, in 1984, new legislation ruled that insured non-member banks could establish or acquire subsidiaries that were engaged in securities activities, including mutual funds, municipal revenue bonds, commercial paper and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Additionally, in 1986, the Federal Reserve reinterpreted Glass-Steagall so that 5 percent of commercial banks’ gross revenue could come from investment banking services (arguing that the term ‘engaged principally’ was not precisely defined, and therefore that commercial banks’ involvement in other activities was open to interpretation). Significantly, when Alan Greenspan became Fed chair in the following year he became a vocal advocate for the end of Glass-Steagall, passing further legislation that allowed banks to expand their securities underwriting activities.10 Legislation and regulation was being peeled back, more and more, Cunha writes that,

“Many states started allowing state-charted banks to participate in securities underwriting, securities brokerage, real estate development, insurance underwriting and insurance brokerage.”

Other policy reforms included the interest rate ceiling being relaxed, real estate lending becoming liberalised with statutory restrictions on lending in this area removed and there was an increase in the number of bank charters granted (as in, literally the number of banks) as the percentage of approved bank applications rose considerably. Finally, the United States started to embrace nationwide branch banking (banking across state lines) which had been prohibited for over half a century prior.11

The result of the Reagan-era deregulation was the savings and loan crisis at the end of the 80s which led to over 1,000 U.S. savings and loan associations (or thrift institutions) failing between 1986 and 1995, producing the biggest series of bank collapses since the Great Depression in 1929.12 Following this, nationwide consolidation throughout the banking sector occurred in the United States, as the top 10 banks increased their commercial assets from 10 to 50 percent between 1990 and 2000.13

Meanwhile, over the pond, towards the end of 1986 came Margaret Thatcher’s ‘Big Bang’ deregulation in the UK; sweeping reforms that prioritised the City and a strong pound ahead of anything else. In order to achieve this, centuries-old guild structures were replaced by an ever expanding global centre of finance and banking. As a result, capital flooded into the City from America, the Middle East, Asia, Europe, practically from anywhere.

“The long bull run”

In the United States, as the Great Inflation was coming to an end and Glass-Steagall was slowly being overturned, another significant event was taking place - “the long bull run”. The “long bull run” refers to increased trading in U.S. government-backed Treasury bonds, as interest rates started coming down, more and more money was pumped into the acquisition of U.S. Treasuries. Long-term bond yields declined from a high of 15 percent in 1981 to 6 percent by the end of the 20th century, leading to higher bond prices and increased trading in U.S. Treasuries. Alongside this, trading in fixed-income securities became ever more important as an anchor to the ever expanding bond market. In the 70s, the OPEC nations and Europe led the way with U.S. Treasury bond purchases, but in the 80s the Japanese (bolstered by huge export surpluses [not least, a large trade surplus with the U.S.] and a domestic real estate boom [Tokyo real estate was worth more than comparable properties in Manhattan]) started purchasing large volumes of U.S. Treasury bonds. This led to huge inflows of foreign capital into the United States, inflows that were more than enough to cover the Reagan-era deficits. America’s recovery after the Great Inflation owed as much to a favourable bond market as it did to “Reaganomics”, the so-called free market or anything else.

The growth of the bond market led to other financial instruments being created, such as asset-backed securities (ABS), mortgage-backed securities (MBS), high-yield corporate bonds (otherwise known as ‘junk bonds’) and others as well. As a result of the end of the Great Inflation, the repealing of Glass-Steagall, the ‘long bull run’ and the Basel Accords, banks’ available capital grew tremendously, it allowed investment banks to scale up their trading in securities, derivatives and in other financial instruments, in a way that wasn't possible before.14

And just like that, the self-reinforcing cycle of money and power had begun, as increased capital flows into Wall Street, London and other financial centres allowed for yet more reinvestment in search of higher returns and new markets. The money flowed in from everywhere, the City boys (on both sides of the Atlantic) were getting richer by the day and no one asked where the money came from.

At the end of the eighties another piece of the shadow banking empire fell into place - the Basel Accords. The Basel Accords lowered capital requirements for banks freeing up capital for more speculative activities in banking and finance. It also laid the seeds for more volatility in the financial system as the safety cushion that banks had to maintain was much smaller now. Additionally, the Accords paved the way for two of the great innovations of shadow banking, securities and derivatives, which as the author Nicholas Shaxson says is, “where things really began to go crazy”.15

The author Adam Tooze remarks that these changes did not happen in a vacuum and that “a trans-Atlantic feedback loop drove down regulation on both sides” of the Atlantic and competition for profit and growth in the 1980s led to a regulatory race to the bottom. Furthermore, he argues that Britain’s deregulation acted as a catalyst to dislodge regulation worldwide. American bankers in the City saw that an axis between Wall Street and the City of London would be the centre of global finance for well into the next century.16

Clinton and beyond

The movement away from regulation reached its climax when President Bill Clinton repealed the remaining parts of the Glass-Steagall Act that had begun in the 1980s.17 This is one of the last significant things Clinton did as president and it led to the Financial Services Modernizing Act (1999), a process that had been underway since the 80s as Clinton concluded what Reagan had started. One central figure in these developments was Robert Rubin who went from co-chairman of Goldman Sachs to the head of Clinton’s new National Economic Council and eventually progressing onto Treasury secretary; Rubin was the link between the Democrats and Wall Street, he went on record saying that Glass-Steagall was obsolete and needed to be revoked.

As a side point, it is important to underline the fact that the overwhelming majority of trade in the shadow banking system is invariably done in dollars thereby reinforcing the strength of the dollar and its position as the world reserve currency. Shadow banking is the invisible hand of the global American empire, a powerful expression of U.S. power and dominance on the world stage.

The reshaping of international finance from the 1970s onwards had tremendous potential for growth but also for instability and volatility.18 Thatcher, Reagan and the Washington consensus shared a deep, unwavering faith in the market-based model of banking and finance but were blind to the threat it posed. These dangers would become reality in 2008 when the global financial crisis struck, the most devastating financial crisis in the modern era (more on this in part two).

Between the years of 1980 and 2007, cross-border capital flows grew at an average annual rate of 14.5 percent, from $1.1 trillion a year to $11 trillion a year. Panitch and Gindin liken this to “an explosion in financialisation”, claiming that the growth in derivatives, equities, demand deposits and government-backed debt securities reached a value of $200 trillion by 2007 (far exceeding trade in actual goods services, it must be said).19 In a somewhat ironic turn of events, since the 2008 crisis the shadow banking system has grown exponentially: in 2010 banking assets were valued at approximately $129 trillion and by 2019 that figure had risen to $155 trillion and it now stands at $188 trillion.20

The figures behind shadow banking can vary tremendously, and estimating the total value of shadow banking is like nailing jelly to the wall. What cannot be refuted, however, is the role that shadow banking has in the world today. Part two will be released in the not too distant future.

Bromberg, M. (2024) Shadow Banking System: definition, examples, and How it works. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/shadow-banking-system.asp.

Ainsworth, B. (2024b) ‘Most Americans are not aware of how concentrated the financial sector has gotten,’ Harvard Law professor says. https://www.hbs.edu/bigs/john-coates-harvard-law-professor-on-the-financial-sector.

Shaxson, N. (2018) The finance curse: How global finance is making us all poorer. Random House., p.33-35

ibid p.54-56

Gindin, S. and Panitch, L. (2013) The Making Of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy Of American Empire. Verso Books., p.169

ibid

Remarks by Assistant Secretary for Financial Markets Joshua Frost on principles of U.S. debt management policy (2025). https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2460.

ibid p.169

Gindin, S. and Panitch, L. (2013) The Making Of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy Of American Empire. Verso Books. P.175

Cunha, J.R. and School of Economics and Finance (2020) The advent of a new banking system in the U.S. - financial deregulation in the 1980s, School of Economics and Finance Discussion Paper Series. report. https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~wwwecon/repecfiles/4/2003.pdf.

ibid p.10

Shaxson, N. (2018) The finance curse: How global finance is making us all poorer. Random House. P.146

Tooze, J.A. (2018) Crashed: How a decade of financial crises changed the world. Penguin., p.54

The Investopedia Team (2022) The Bond Market: A Look Back. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/06/centuryofbonds.asp

Shaxson, N. (2018) The finance curse: How global finance is making us all poorer. Random House., p.150

ibid p.82

ibid p.54

ibid 84-5

Gindin, S. and Panitch, L. (2013) The Making Of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy Of American Empire. Verso Books. P.284-5

Statista (2025) Assets of banks worldwide 2002-2023. at https://www.statista.com/statistics/421215/banks-assets-globally/.

Fantastic work (again). The City of London is rotten to the core but with hindsight shadow banking seems inevitable result after we left the gold standard. Their machinations led to the 2008 crisis l feel. I am looking forward to part two.

We done for a solid piece. My financial knowledge is very small. I've read Niall Ferguson's Ascent of Money. From what I gather, economics and finance was far more easier to understand before the 80s. I don't think I will ever truly get my head around it all.